This is the second part of a two part review of Mark Johnston’s Surviving Death. Part 1 is here.

N arratives of Personhood

arratives of Personhood

In the third Surviving Death lecture, Johnston asks why the boundaries of the intentional self ‘roughly’ coincide with those of the living human organism, and answers:

It is because we have been brought up inside the narrative of the human being, a narrative which…tells us roughly how long we can expect to last…. This narrative, which forms a frame around our collective life, makes what could otherwise strike us as tendentious identifications of a consciousness or an arena across periods of deep sleep or unconsciousness seem utterly natural. In making such identifications we make them true or at least immune to refutation. [Johnston, 2010, p 247]

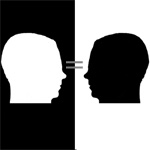

The boundary of the person, that circumscribes our self-concern, is a product of culture. To bring the point to life, Johnston imagines three populations in which different boundaries of personhood are accepted: the Hibernators, the Teletransporters, and the Human Beings.

The Hibernators are intelligent, culturally modern human beings with a genetic quirk that keeps them constantly awake for most of the year, but puts them soundly to sleep during the coldest months. Although the Hibernators are well acquainted with the facts that their organisms normally survive the winter slumber, they do not regard the lives to be lived next year as their own. They do not anticipate having the experiences of those who will wake in the spring, and therefore do not fear such of those experiences as are expected to be painful, or look forward with expectant delight to experiences that will be delightful. Despite the fact that next year’s Hibernators will have veridical memory-like experiences of the lives of this year’s Hibernators, they will not regard those remembered lives as their own. A Hibernator does not take personal pride in his predecessor’s achievements, or feel guilty about his transgressions.

The Teletransporters are a technologically advanced human culture who rely on teleportation for transportation over long distances. When planning trips, they unproblematically extend their self-concern to their reconstructed successors. The successors pay their predecessors’ debts, and bask in their glories.

And the third group, we, the Human Beings

…regard Teletransportation as a form of human Xeroxing that has the unfortunate feature of destroying the original. At first, it seems to us that the Teletransporters…are prepared to commit suicide and even kill their own children by putting them into the machine. [Johnston, 2010, p 262]

The Teletransporters know the machine destroys their original bodies. They just don’t care. Continue reading “Being Protean – Johnston’s Narratives of Survival”