Here I am again.

I say “I” hesitantly, given the context. Anyway, this self-same bundle of attributes, having lost and gained more than a few (attributes) over the years, persists with enough continuity to be recognized as the same person.

I did not die of melanoma. With the help of state-of-the-art immunotherapy, my immune system made short work of the cancer. But my ramped-up, unleashed immune system also destroyed my thyroid, and my thyroxine levels fell to levels that are clinically rare. Thyroxine controls the body’s metabolic rate, and therefore everything. I was treated for hypothyroidism, but not before falling into a deep depression, which left me unable to write, or think, or even compose a simple email without revising it for hours. Here is a fragment of writing from that time I found this morning in an old file:

Yesterday I thought I could perhaps write again, another blog post. But the attempt seems to have cast me into the pit of despair. I wanted to do something simple and clear, something I could be proud of.

Anyway, that explains my absence. The road to recovery was long, involving physically-demanding tasks far removed from the philosophy of personal identity. This past summer, I finally began to think about taking up this project again. Then I got an email out of the blue (or whatever colour cyberspace is). It started out

Hi Gordon,

I want to thank you for so clearly and plainly

explaining this idea of self-concern in your

illusion of survival post. Before I found it

I had been searching for a way to positively

conceptualize the possibility that Parfit's

extreme claim was real. I've now read that post

many times and a number of your other posts from

the blog. I've shared the illusion of survival

post with many of my friends but it seems it

doesn't fascinate them as it does me.

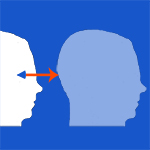

That hooked me. I have friends like that too. The email was from Scott Emerson. Scott said he wanted to “somehow make the illusion of survival post into a video for people who aren’t interested enough to read very much.” We started corresponding, met on Zoom. Scott’s video went through several drafts. This week he published it on YouTube.

It’s interesting and rewarding to see someone else’s sympathetic take on ideas you have worked with a long time. Scott’s lens is not my lens; he says things I wouldn’t say, and says things I would say in ways I wouldn’t think of saying them. That is to be expected. We are different people, with different backgrounds. Variation adds depth to the topic, and broadens its appeal. Scott’s video grew from seeds planted by Parfit, by William Hazlitt, by Nagarjuna, seeds of the same lineage that sprouted as the Phantom Self blog. The existence of Scott’s video proves that the seeds remain viable; this is a life form that can survive and thrive in the competition of ideas. I invite you to watch it. It is also in text form here. As always, both Scott and I welcome your comments.