Is a viral meme thwarting social progress?

To me Goldstine said, “Kid, don’t listen to him. You live in America. It’s the greatest country in the world and it’s the greatest system in the world. …. He tells you capitalism is a dog-eat-dog system. What is life if not a dog-eat-dog system? This is a system that is in tune with life. And because it is, it works. Look, everything the Communists say about capitalism is true, and everything the capitalists say about Communism is true. The difference is, our system works because it’s based on the truth about people’s selfishness, and theirs doesn’t because it’s based on a fairy tale about people’s brotherhood. …. We know what our brother is, don’t we? He’s a shit. And we know what our friend is, don’t we? He’s a semi-shit. And we are semi-shits. So how can it be wonderful? Not even cynicism, not even skepticism, just ordinary powers of human observation tell us that is not possible.” —Philip Roth, from I Married a Communist

In 2011, the political dialogue became about rampant inequality, framed by the Occupy movement as a struggle between the 99% and the 1%.

If only it were that simple. Even in an imperfect democracy, a genuine class struggle between 1% and 99% should be a foregone conclusion. Yet the status quo persists, because large numbers of the 99% don’t see anything wrong with it. Those who do are frustrated to watch, in election after election, too many people voting against their own economic interests.

Part of the reason may be the Steinbeck effect. As John Steinbeck observed about the difficulty of organizing for change in the Dirty Thirties, “I guess the trouble was that we didn’t have any self-admitted proletarians. Everyone was a temporarily embarrassed capitalist.” [Steinbeck, 1966] This attitude was evident in a letter to the editor beginning, “I do not deride the 1 per cent; I am motivated to join their ranks.” [Globe and Mail, 2011]

But wishful thinking is not the whole story. Plenty of lifetime members of the 99% have no aspiration to join the more exclusive club. They include most of the middle class who voice no objection to their now-endangered status. There is a deeper problem: they have swallowed an idea.

I call this idea “the dark doctrine of the political right.” It is “dark” in two senses: as in “the dark side,” obviously, but also as in “dark matter.” Dark matter neither glows nor reflects light, and is therefore invisible. From its gravitational effects, it is believed to constitute 83% of the matter in the universe. Some ideas are like that too: invisible, because assumed without any conscious weighing of evidence, yet exerting a gravitational pull on behaviour.

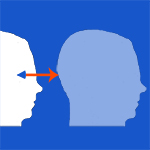

The Dark Doctrine is the idea that all human motivation is fundamentally selfish—that we act out of self-interest and nothing else. Although some people may appear to value moral principles, or to be moved by sympathy for others, they only do so because ‘it makes them feel good.’ At bottom, we’re all driven by the desire to feel good. Selfishness drives all. Continue reading “The Dark Doctrine of the Political Right”